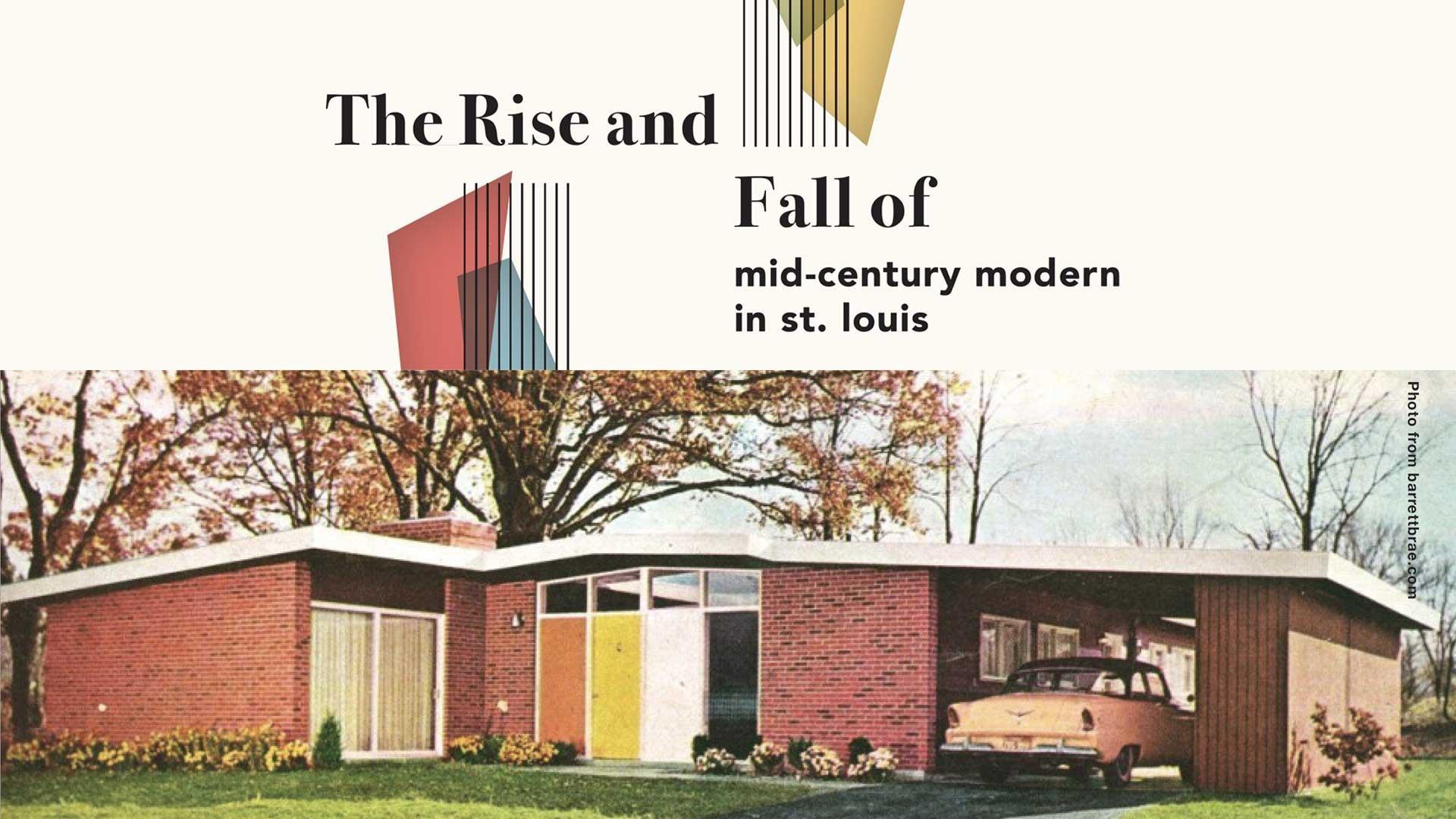

The hour-long Nine special tells the human stories behind the progressive vision mid-century modern architecture ushered in after World War II.

Sometimes it takes a generation or two removed from an architectural style to appreciate it. Such is the case of midcentury modern. Mid-century modern is a style of design, from roughly the 1930s through the mid–1960s, characterized by clean lines, organic and streamlined forms, and lack of embellishment. It reached is height of popularity after World War II, where it was used in residential structures, with the goal of bringing modernism into America's post-war suburbs.

For Mid-Century Modern in St. Louis writer/producer Kara Vaninger, the story of mid-century modern architecture isn’t just about buildings and artistic vision, it’s about a hopeful time when a new consciousness about how our lives could change for the better was taking hold.

The modernist movement was born of a changing world. The world had been through two World Wars and veterans were seeking a new way of life. “Modernism promised a break from formality...and helped the middle class gain a foothold,” says Vaninger.

Nowhere was that more evident than in the St. Louis suburbs. Modernist design was viewed as a democratizing style and it naturally appealed to Americans. Modernism represented progress and a break from tradition.

Ralph and Mary Jane Fournier not only designed modernist homes in St. Louis, they built entire neighborhoods. The hundreds of homes in Chesterfield, Crestwood, Creve Coeur, Kirkwood, and Des Peres built in the years after World War II are fine examples of the mid-century modern residential architecture style. They were modular, so they were easy to erect, and purposefully built to obstruct unsightly views, take advantage of natural light, and have minimal impact on their natural, parklike settings.

Many synagogues and churches in St. Louis were also built in the modernist style during this time to forge their own identities and distinguish themselves from Christian churches.

St. Louis becomes hotbed for modernism

The human story of the history of this built environment in St. Louis interweaves World War II and Japanese internment camps.

“WWII was a catalyst for a lot of what happened,” says Vaninger. Famous European architects and teachers of the Bauhaus and International styles of architecture were fleeing the Nazis for the freedom of the U.S. Returning veterans on the GI Bill were entering schools like the School of Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, which became a hotbed of modernist architecture.

Young Japanese Americans were given the opportunity to enter schools in the Midwest and East Coast to avoid internment camps. Dramatically, Gyo Obata joined the student body at Washington University the night before his family, living in California, was sent to a prison camp. Obata went on to design the McDonnell Planetarium, GROW Pavilion at the Saint Louis Science Center and the Saint Louis Abbey and Priory School.

But the “modern” philosophy had downsides, too. Even before WWII, 30 city blocks near the riverfront were cleared in the name of progress; Victorian architecture was destroyed and an African American neighborhood displaced. The land eventually became the site for the Gateway National Park.

Eero Saarinen’s winning entry for the Jefferson Memorial was a big moment for the modernist movement. It signaled that classical forms of architecture were no longer the only option and progressive ideas were welcome.

On dedicating the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial on May 25, 1968, Vice President Hubert Humphrey remarked, “Let the Gateway Arch stand, then, as a symbol of America's determination to have beauty with utility…quality with quantity…and humanity with progress. …From now on, St. Louis will be ‘living up to the Arch.’''

By the late 1960s and 70s, modern architecture and design was becoming “normative, moderate, even conservative,” says Michael Allen, academic researcher, historian, teacher at Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, Washington University in St. Louis.

Many modernist structures were overlooked for preservation, despite being more than 60 years old, and have been torn down. “What I realized through all of the interviews was how much modern architecture and thought affected our city,” says Vaninger.

Now, a new generation has taken the mantle for preserving and telling the stories of mid-century modern architecture in St. Louis.

This article first appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of nineMagazine.

The production is supported by Mackey Mitchell Architects.