Content note: Nine PBS will be featuring stories that center on the experiences and voices of LGBTQ+ St. Louisans throughout the month of October to celebrate LGBTQ+ History Month. If there are any organizations, businesses, or individuals you think have contributed to the LGBTQ+ community, let us know by emailing Molly Hart at mhart@ninepbs.org.

Contributed by Molly Hart, Social Media Coordinator

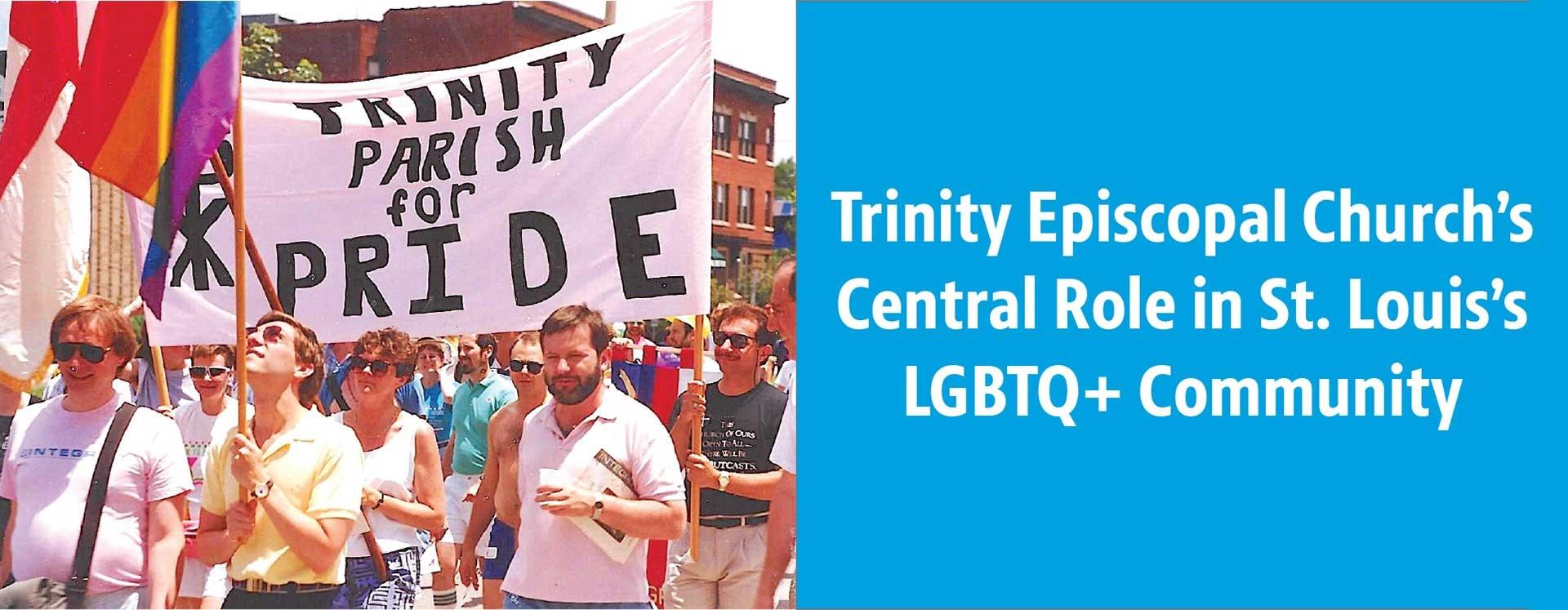

Religious institutions are not always friendly to LGBTQ+ people. But Trinity Episcopal Church, at the corner of Euclid and Washington, has been at the center of St. Louis’s fight for queer rights. So much so that in 2021, the church was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

However, the church was not always as bustling as it is today. In the 1950s, the neighborhood around Trinity saw an influx of Black and gay residents as the city’s landscape evolved. The church was facing a decline in attendance, but instead of shutting its doors, they opened them wider. Choosing to embrace the evolving community marked a turning point in its journey to becoming a safe space for LGBTQ+ activism and community events.

Halloween 1969

A pivotal moment in Trinity's LGBTQ+ advocacy came on Halloween night in 1969. Greg Smith and a group of friends decided to celebrate the holiday by dressing as women and visiting a local bar called the Onyx Room. However, their night took a turn when the police arrested them, charging them with masquerading. (At the time, St. Louis had laws against wearing clothes of the opposite sex, making this a serious legal issue. St. Louis was the first city in the country to have laws against cross-dressing, according to a Washington Post article. The laws were created in 1843 and lasted into the 1980s.)

Smith’s recollection of that night was vivid when he shared his story with a crowd outside the church in 2021. He and his friends found themselves in a paddy wagon, unsure of why they were being arrested until they reached downtown St. Louis. That's when they were informed of the charges. The police wanted Smith to remove his wig and walk out "like a man." But Smith, in a purple dress and gold pumps, stood his ground.

“So, I got out my compact, teased my wig, and said, 'I’ll walk out the way I came in,'” Smith remembered.

The events of this night unfolded at a time when queer rights were in their infancy. Only a few months before the incident, St. Louis witnessed the formation of its first gay rights group, the Mandrake Society. Trinity Episcopal Church hosted the society’s monthly meetings there, playing a pivotal role in supporting them. The Mandrake Society did not just provide general support for the gay community. They also offered legal aid, including raising bail money for individuals like Smith, who found themselves in legal trouble because of their identity and clothing choices.

The church’s place in history

Trinity's commitment to LGBTQ+ advocacy extended beyond these acts of solidarity. In 1969, Ellie Chapman became a member of Trinity Church, where her late husband, Reverend Bill Chapman, was a prominent leader in these progressive efforts. Reverend Chapman served as rector for two decades and was instrumental in caring for the city’s first AIDS patients during the 1980s. The church's involvement in LGBTQ+ rights and healthcare marked it as a pillar of compassion and acceptance in the community. Ellie said she was proud of her church for so quickly putting themselves at the center of the LGBTQ fight for equality.

"I remember walking out of a service one day, coming down the front steps, just as the very first pride parade passed by here," Ellie said.

Trinity Episcopal Church's recognition on the National Register of Historic Places is not merely about preserving a beautiful building; it's about honoring a legacy of advocacy and acceptance. This church, nestled in the heart of St. Louis, has played a crucial role in the city's LGBTQ+ history. Trinity's journey is a reminder that historic places are not defined solely by their physical structures, but by the profound impact they have on the lives of those in their community.

This story originally appeared in a 2021 episode of Living St. Louis, produced by Brooke Butler.